By Serena Covkin, PhD for the Evanston Women’s History Project, March 2025

Alice Bunker Stockham was a popular physician, a pioneering social reformer, a world-traveling educator, and Evanston’s first certified tokologist. She assumed the role in 1883, when she reworked the Greek word for “birth” into the title of her first medical advice manual, Tokology: A Book for Every Woman. She hoped it would help her readers endure “the sufferings peculiar to their sex.” (1) According to Stockham, these included not only menstruation, pregnancy, and labor and delivery, but also overly demanding husbands and the dictates of women’s fashion (she hated corsets and impractical shoes). (2) By the time she arrived in Evanston in 1890, Tokology had already sold more than 150,000 copies in the United States and all around the world. (3) And from Evanston, first in a house on Burnham Place and then on Ridge Avenue, she only expanded her output and her reach even more. (4) Eventually, ironically, it was this success that earned Stockham the attention of government censors and a (controversial) conviction in federal court. Until then, however, she helped shape her adopted community—and helped create a society in which future women physicians, reformers, and educators could thrive.

Stockham was already 50 years old when she published Tokology. She was born in 1833, in Ohio, to parents who both practiced the teachings of the herbalist Samuel Thomson. (5) Even as a young girl, in other words, Alice Bunker learned that men and women could help restore the sick to good health, and became familiar with various indigenous, natural, and otherwise alternative remedies. (6) In 1853, she entered a degree program at the Eclectic Medical Institution in Cincinnati, where she met her husband, Gabriel Stockham, and became one of the first female physicians in the country. (7) Over the next two decades, the Stockhams raised two children together while championing homeopathic cures side by side, first in Lafayette, Indiana and then in Leavenworth, Kansas. (8) In both cities, Alice worked to educate and empower the women she encountered, not only addressing their immediate healthcare needs but also organizing intimate “parlor talks” on the female body and its particular problems. (9)

It wasn’t until the late 1870s, after moving to Chicago, that Alice’s ambitions grew larger still. Surely, her diminishing domestic obligations played a role: by that time, her children had grown up, and not long after they’d both arrived in Chicago, Alice and Gabriel had gotten divorced. (10) Suddenly on her own, Stockham started lecturing to larger and larger crowds, and staking out more forceful and more challenging positions. Speaking to a meeting of the Illinois Social Science Association in 1878, for example, she declared that “‘no girl should go to the altar of marriage without being instructed in the physiological function of maternity.’” (11) Three years later, speaking at the Third Unitarian Church on the West Side of Chicago, she connected her plea for comprehensive sex education to her larger fight for women’s equality. She explained that understanding their own reproductive capacities was key to women’s “‘good health,’” and that protecting their “‘good health’” was key to women’s social, political, and economic advancement. (12) Without it, women would literally—physically—never be able to keep up.

In the early 1880s, Stockham went back to school, earning a degree from the Chicago Homeopathic College in 1882. (13) And in 1883, she published Tokology, bringing her wealth of medical knowledge—and a few of her kookier ideas—to an exponentially wider audience.

Nowadays, Tokology seems even more interesting because of this mix: of the forward-thinking and the out-of-date, the clearly factual and the frankly bizarre.

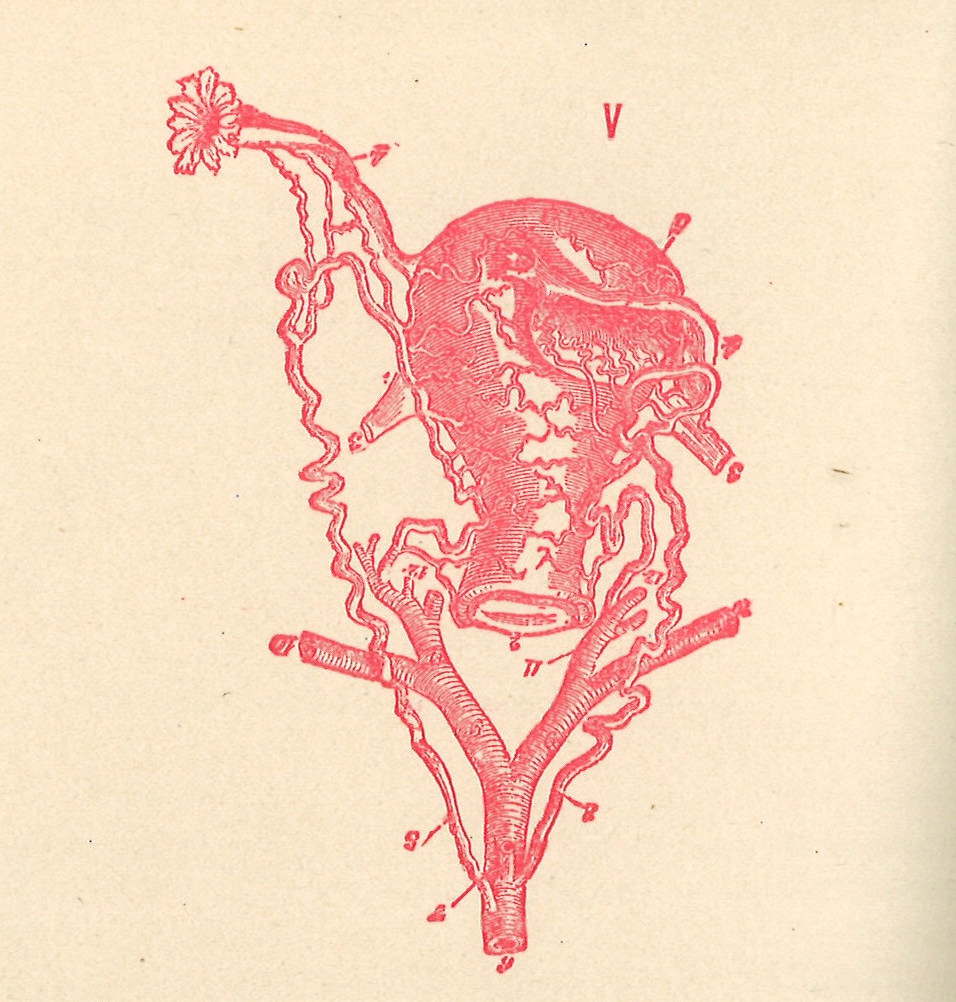

In the book’s first chapters, for example, Stockham matter-of-factly explained how a woman’s body changed during pregnancy and childbirth, introducing her readers to scientific terms (like “ductus arteriosus”) that they most likely would have never encountered before. (14) She likewise taught them how to mitigate pregnancy’s worst side effects, how to avoid the common causes of miscarriage, and how to recognize the common signs of menopause. (15) Perhaps most striking, Tokology’s final section featured a series of detailed anatomical sketches that, apart from their being hand-drawn, would fit right into a medical textbook today. (16) In an era when (mostly male) physicians regularly railed against women’s higher education by arguing that overtaxing their brains would impair women’s reproductive organs, Tokology implicitly and explicitly argued the opposite: that learning the truth about their own bodies would help women enjoy a healthier pregnancy and an easier delivery. (17)

At the same time, Tokology’s theories of “painless childbirth” were themselves rather outlandish. For example, Stockham suggested that foreign-born and non-white women suffered far less during labor and delivery. (18) She also promised that white women could experience the same relative comfort—not by taking pain medication, but by eating, drinking, dressing, and exercising exactly as she prescribed, sometimes for decades before they became pregnant. (19) Notably, Stockham also argued against the idea that only men should enjoy, and that women should merely endure, sexual intercourse. (20) But she also offered up new ways that her readers might refuse—or else transmute—their husbands’ sexual advances. For example, she endorsed what she called “the ‘law of continence’” (or sex without ejaculation), and further cautioned husbands and wives against sleeping together during and after pregnancy, warning that if they did, they would inevitably conceive even more “puny,” “nervous,” and “sickly” children. (21) In other words, all throughout Tokology, Stockham tried to help vulnerable women take care of their own health and wellbeing, but she also relied on now-baffling ideas about race, reproduction, and heredity to do so.

These now-baffling ideas were widely held in the late nineteenth century, however—not only by doctors and healers, but also by suffragists and other social reformers, by a growing number of public intellectuals, and by a growing array of spiritual thinkers. (22) Alice Bunker Stockham was all of the above. And Tokology was an enormous hit.

In the book’s first decade in print, it sold at least 150,000 copies, and possibly many more. (23) In 1892, an advertisement running in the pro-suffrage newspaper The Woman’s Tribune claimed that it had sold 200,000. (24) It was translated into Finnish, French, German, Swedish, Japanese, and Russian. (25) Leo Tolstoy, who shared Stockham’s interest in post-pregnancy celibacy, personally organized and wrote a new preface for the Russian language edition. The novelist also invited Stockham to visit him in Russia—which she did—while becoming a veritable world traveler. (26) In the 1880s and ’90s, after publishing Tokology, she made multiple trips all throughout Europe and Asia, learning, lecturing, and networking with women’s rights activists everywhere she went. (27)

Even still, in many ways, the connections that Stockham now started to forge in and around Chicago were even more important. For example, it was in Chicago that she got to know Moses Harman and Ida Craddock, two so-called “sex radicals” who helped shore up Stockham’s commitment to censorship-free sex education. (28) It was also in Chicago, in 1886, that she befriended Emma Curtis Hopkins, an up-and-coming leader in the burgeoning “New Thought” movement. (29)

Stockham quickly became a believer in New Thought as well, and vice president of Hopkins’s “Metaphysical Association.” (30) Like other New Thought-ists (and much like self-help experts and influencers today), Stockham started to promote the idea that ordinary human beings could help create a more perfect world with the power of their minds—and, specifically, with the power of positive thinking. (31) She never abandoned her scientific training by any means, but from the mid-to-late 1880s on, she increasingly emphasized that mental healing was part and parcel of physical healing. For later editions of Tokology, for example, Stockham wrote a new section titled “Mind Cure A Reality.” (32)

It was also in these same post-Tokology years that Stockham took on a totally new role: entrepreneur. Stockham and her daughter Cora established the Alice B. Stockham Publishing Company in 1887. (33) It released those later editions of Tokology, the articles and essays of other New Thought writers, and a whole slew of books on women’s reproductive health. (34) (An advertisement once called the Stockham Company “‘the only [publishing] house in America devoted entirely to Sexual Science.’”) (35) Notably, Stockham saw the firm not only as an opportunity to empower her female readers, but also as an opportunity to empower young working women, whom she went out of her way to hire as door-to-door “book canvassers.” (36) And, evidently, Stockham benefitted financially as well: when she moved to a “lakefront property” in Evanston, in 1890, it was without a breadwinning husband, and with her adult daughter, two nieces, and three domestic servants in tow. (37)

The company’s offices remained downtown, but Stockham continued to manage matters from the North Shore. (38) In fact, the firm’s offerings only grew after she moved to the suburbs—in no small part because Stockham herself published more and more. While Tokology continued to sell thousands of copies every year, she also wrote a new novel, several books of essays, and several more advice manuals for young girls and married couples—all from her home in Evanston, and all in her sixties and seventies. (39)

It was also in Evanston that Stockham was finally able to devote herself to the day-to-day reform work that had long animated so much of her writing. For example, after years as a speaker and author focused on young women’s coming-of-age, she became more directly involved in their education. In 1894, she founded a Back Lot Society for Evanston’s teen girls—modeled after a similar group that already existed for teen boys—which regularly invited “[e]minent persons” to give lectures on “literary and educational subjects” in her own home. (40) Together with her daughter Cora, she also opened the Stockham Park Kindergarten, published a Kindergarten Magazine, and helped introduce slöjd (a Scandinavian method for teaching arts and crafts and design) to Chicago public school curricula. (41)

Stockham also collaborated with newfound Evanston friends, like Frances Willard (then the president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union) and Elizabeth Boynton Harbert (one of the founders of the Woman’s Club of Evanston), who shared her same interest in women’s equality. Both Stockham and Willard, for example, became founding members of the Illinois Woman’s Press Association, for which Stockham is said to have hosted lavish annual picnics. (42) Stockham and Harbert, meanwhile, not only co-coordinated events for the Woman’s Club (like a hands-on demonstration of “how to cook in an emergency”), but also co-hosted meetings for the Hopkins Metaphysical Association. (43) And, all the while, Stockham continued to lecture: at churches, women’s clubs, and mother’s clubs, and at august local institutions like the Masonic Temple (then the tallest building in Chicago) and the Chicago Institute of Education (alongside Jane Addams, who co-founded Hull-House). (44)

It was in Evanston, in other words, that Stockham most enjoyed the fruits of her labor and became best known, not only as a well-respected public figure, but also as an important member of her local community. She never stopped teaching women—in plain language and in public—about their bodies and their health. If anything, in Evanston, she became even more forthright, and even more committed to the cause. (45) That commitment endeared her to medical experts and social reformers, to her neighbors along the North Shore, and to ordinary people all over the world. It made her famous and well-to-do. But it also made her vulnerable—and in the spring of 1905, her writing finally reached the wrong readers: U.S. postal inspectors on the lookout for “obscene, lewd, and lascivious” mail. (46)

Of course, Stockham can’t have been too surprised by her arrest. The legislation under which she was charged—the federal Comstock Act, named for notorious anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock—had been on the books since 1873 (and, by the way, it’s never been repealed). (47) Her friend and fellow activist Ida Craddock had already been indicted on the same grounds three years earlier, and all together, Chicago-area prosecutors had already tried almost 500 such cases. (48) In fact, it was precisely because federal officials were so intent on repressing information about sex and reproduction that Stockham was so intent on spreading it far and wide. But if she wasn’t surprised, she also wasn’t worried—or at least not at first. (49)

Stockham quickly hired defense attorney Clarence Darrow, who would later go on to defend the Tennessee high school teacher under attack in the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” and who was already rather famous. (50) Throughout her own trial, Stockham maintained (in various public remarks) and Darrow claimed (in court) that her writings were scientifically accurate, aimed at education rather than at titillation, and most important, nothing new. (51) After all, she’d been circulating the same kind of material, without complaint, for over 20 years—ever since she’d first published Tokology.

Their legal arguments made sense. Supporters, including many Evanstonians, regularly cheered her on in the courtroom. But the jury was unmoved. Stockham was found guilty and, though not sentenced to prison, made to pay a heavy fine. (52)

For at least a few more years, Stockham continued to write, and continued to lay plans for circumventing the Comstock Act and its enforcers. (53) But they were all for naught. Her publishing company went out of business, her speaking engagements dried up, and her already-published works became immediately less popular. (54) Even Tokology wasn’t spared. (55)

In 1910, five years after her obscenity trial, Alice and her daughter Cora moved across the country to Alhambra, California. Two years after that, Alice Bunker Stockham passed away. (56)

Now, more than 100 years later, most Americans couldn’t tell you how Alice Bunker Stockham fought to transform women’s lives, or how she helped them address the physical problems and the societal barriers they faced. But here in Evanston, her legacy still lives on.

1 Alice B. Stockham, dedication in Tokology: A Book for Every Woman, 2nd ed. (Chicago: Sanitary Publishing Co.,

1884).

2 Stockham, Tokology, 2nd ed., i-v, 83-95.

3 Beryl Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom: American Women, Sexual Purity, and the New Thought Movement, 1875-1920

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 136-137.

4 Janet G. Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her Efforts,” undated, in “STOC,”

Evanston History Center Biographical Files.

5 Marsha Silberman, “The Perfect Storm: Late Nineteenth-Century Chicago Sex Radicals: Moses Harman, Ida

Craddock, Alice Stockham and the Comstock Obscenity Laws,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 102,

no. 3-4 (Fall-Winter 2009): 329. 6 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 329; Joanna Smith Weinstock, “Samuel Thomson’s Botanic System: Alternative

Medicine in Early Nineteenth Century Vermont,” Vermont History 56, no. 1 (Winter 1988): 5-22.

7 Accounts differ as to whether or not Alice Stockham formally graduated from the Eclectic Medical Institution. See,

for example, Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 135; Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 329; and Jennifer Wilson, “The

Revolution Will Not Be Consummated: The Politics of Tolstoyan Chastity in the West,” The Slavic and East

European Journal 60, no. 3 (Fall 2016): 499.

8 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 135; Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 329.

9 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 329; Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her

Efforts,” undated, in “STOC,” Evanston History Center Biographical Files.

10 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 329-330; Find a Grave, database and images

(https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/263992789/cora-skaife: accessed February 25, 2025), memorial page for

Cora Stockham Skaife (1857–20 Aug 1920), Find a Grave Memorial ID 263992789, citing Angelus Rosedale

Cemetery, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, California, USA; Find a Grave, database and images

(https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/95506589/william_henry-stockham: accessed February 25, 2025), memorial

page for William Henry Stockham (15 Sep 1861–16 Nov 1923), Find a Grave Memorial ID 95506589, citing

Elmwood Cemetery and Mausoleum, Birmingham, Jefferson County, Alabama, USA.

11 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 330.12 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 330.

13 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 330; “DR. ALICE B. STOCKHAM,” December 1912, in “STOC,” Evanston

History Center Biographical Files.

14 Stockham, Tokology, 2nd ed., 9-74.

15 Stockham, Tokology, 2nd ed., 27-136, 225-233, 267-286.

16 Stockham, Tokology, 2nd ed., [pages unnumbered].

17 Vern Bullough and Martha Voght, “Women, Menstruation, and Nineteenth-Century Medicine,” Bulletin of the

History of Medicine 47, no. 1 (January-February 1973): 66-82.18 Stockham, Tokology, 2nd ed., 1-8, 22-23, 159-161.

19 Stockham, Tokology, 2nd ed., 1-8, 75-136, 150-177.

20 Stockham, Tokology, 2nd ed., 138-139.

21 Stockham, Tokology, 2nd ed., 137-149.

22 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 1-19; Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 324-367; Wilson, “The Revolution Will Not

Be Consummated,” 494-511; Carolyn Skinner “‘The Purity of Truth’: Nineteenth-Century American Women

Physicians Write Delicate Topics,” Rhetoric Review 26, no. 2 (2007): 103-119.23 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 136.

24 Skinner, “‘The Purity of Truth,’” 103-104.

25 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 136; Skinner, “‘The Purity of Truth,’” 103-104.

26 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 322-323; Wilson, “The Revolution Will Not Be Consummated,” 495.

27 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 137.

28 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 324-325.

29 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 136; Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 331.

30 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 136.

31 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 2-4.32 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 136-138.

33 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 136.

34 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 136-137.

35 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 348.

36 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 136-137; Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 330-331.

37 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 138; Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her Efforts,”

undated, in “STOC,” Evanston History Center Biographical Files.

38 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 331.

39 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 137-149; Wilson, “The Revolution Will Not Be Consummated,” 499.40 “NEWS NOTES,” December 29, 1894, in “STOC,” Evanston History Center Biographical Files.

41 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 113, 137; Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her

Efforts,” undated, in “STOC,” Evanston History Center Biographical Files.

42 Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom, 137; Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her Efforts,”

undated, in “STOC,” Evanston History Center Biographical Files.

43 Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her Efforts,” undated, in “STOC,” Evanston

History Center Biographical Files.44 Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her Efforts,” undated, in “STOC,” Evanston

History Center Biographical Files.

45 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 343-346.

46 18 U.S.C. §1461 (2025); Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 348.

47 18 U.S.C. §1461 (2025); Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 348.

48 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 324.

49 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 348.50 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 348.

51 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 348-349; Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her

Efforts,” undated, in “STOC,” Evanston History Center Biographical Files.

52 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 348-349; Messenger, “Pioneer Doctor Educates Women, Goes On Trial for Her

Efforts,” undated, in “STOC,” Evanston History Center Biographical Files.

53 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 349-351.

54 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 349-352; “DR. ALICE B. STOCKHAM,” in “STOC,” Evanston History Center

Biographical Files.

55 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 349-352; “DR. ALICE B. STOCKHAM,” in “STOC,” Evanston History Center

Biographical Files.

56 Silberman, “The Perfect Storm,” 352; “OBITUARY: Dr. Alice B. Stockham,” December 14, 1912, in “STOC,”

Evanston History Center Biographical Files.