By Sophia Weglarz, Summer 2021 Evanston Women’s History Project Intern

My name is Sophia Weglarz. I am a current undergraduate student at the University of Pennsylvania studying cognitive neuroscience and Africana Studies. While I have worked with the Evanston History Center and the Evanston Women’s History Project in previous summers, this summer I have the unique opportunity to work as an intern with the Evanston Women’s History Project. My work this summer, as it did in previous summers, centers around the narratives that are integral to African-American history in Evanston. This summer, I started my work with a focus on Maria Murray, the first Black resident of Evanston.

Murray’s story is particularly captivating, as what we knew about her life previously was often intertwined with a narrative of fragility and white benevolence. While early white allyship played a role in Maria’s life, putting this theme at the forefront takes away from the compelling story of who Maria Murray was.

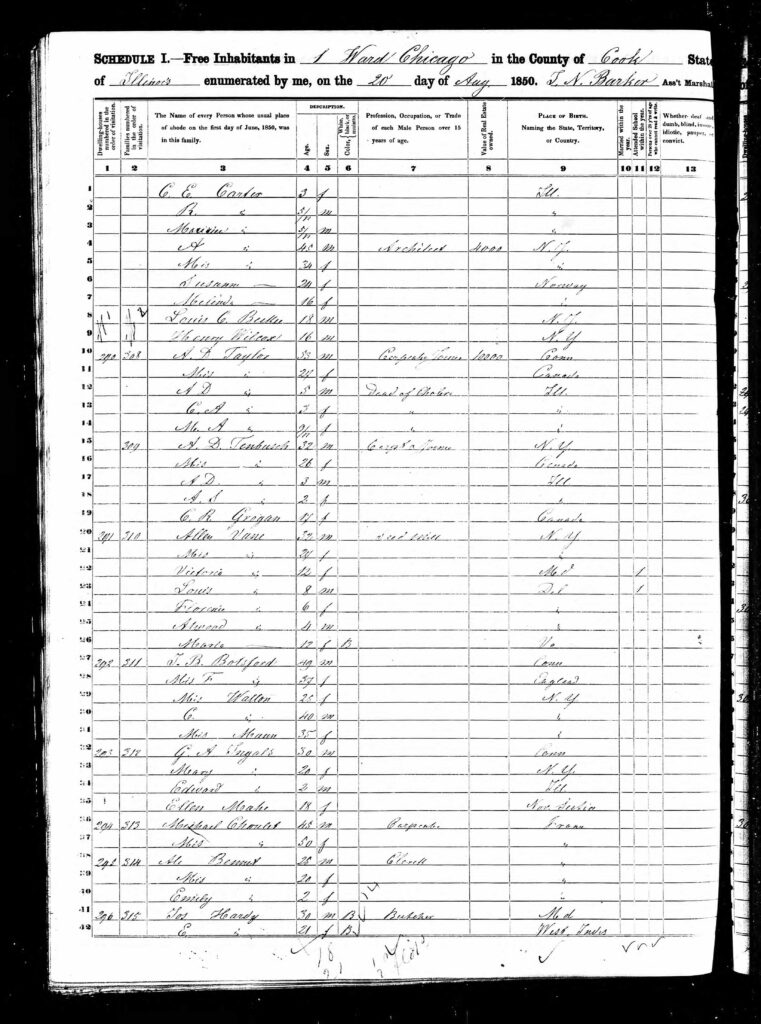

Maria Murray was born in the late 1830s to the early 1840s, as an 1850 Chicago Census lists her as 12 at the time.[i] In multiple censuses to follow, her birthplace is often either listed as Virginia or Maryland. Maria came to Illinois when Allen and Mary Vane, both born in Cambridge, Maryland, bought her freedom and traveled with her to Chicago in the late 1840s.[ii]

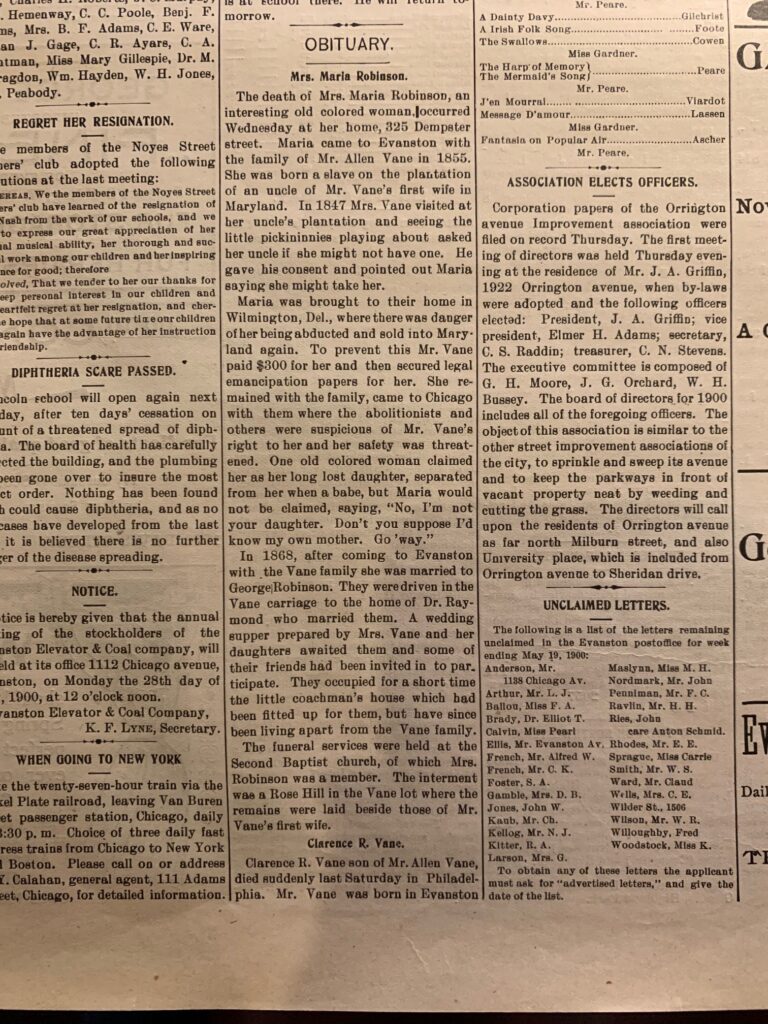

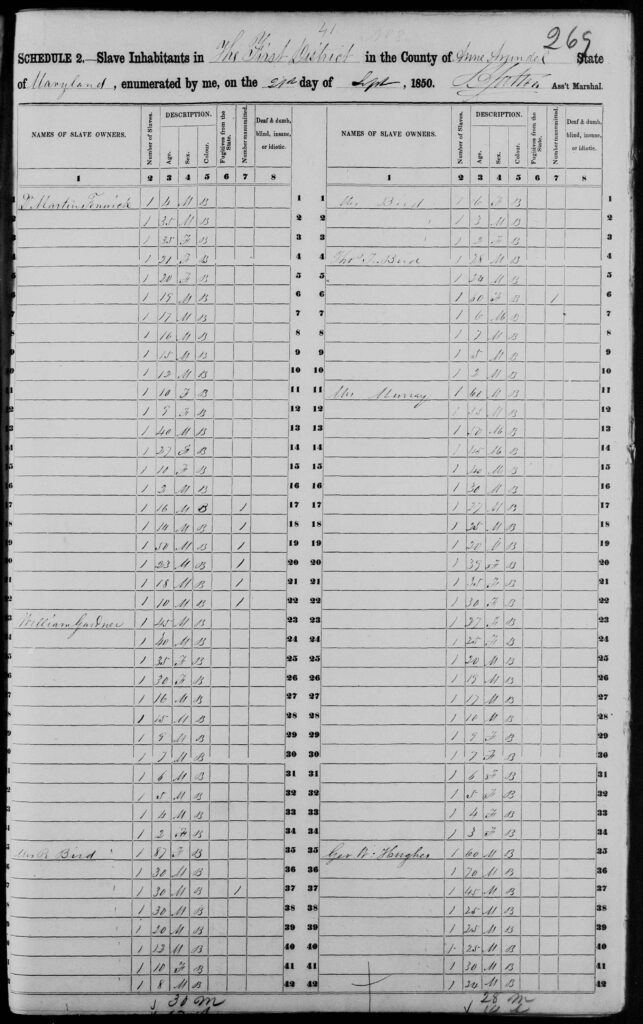

How Maria came into the Vanes’ possession is unclear. An anecdote told in Maria’s 1900 obituary states that Mary Vane saw Maria at her uncle’s plantation in a group of “pickaninnies” and “asked if she could have one.” Mary’s uncle agreed and told her that she could have Maria.[iii] While there is no evidence to suggest that this story is true (there is no indication that Mary Vane even had an uncle) there is an 1850 slave schedule of a ‘Murray’ family living in the Cambridge, Maryland area that records several young female slaves, a few of which could match Maria’s age at the time.[iv]

Accordingly to Maria’s obituary, after Maria came into the Vanes possession, she was brought to their home in Wilmington, Delaware, where there remained a high likelihood of her being sold back into the slave trade. To prevent this, Allen Vane paid $300 for her, which is equivalent to $10,488 in today’s money, and then secured legal emancipation papers for her. These records have yet to be found – and much of this early story cannot be substantiated.

When Maria came to Chicago in the late 1840s, Illinois had laws restricting the movements of former slaves. Though a “free” state, former slaves needed to register and there were limits on how many could move to Illinois in any year. Several abolitionists and others were suspicious of Mr. Vane’s right to Maria and questioned her status. Her safety was threatened. One older Black woman claimed her as her long lost daughter, separated from her when a baby, but Maria would not be claimed, saying, “No, I’m not your daughter. Don’t you suppose I’d know my own mother. Go away.”

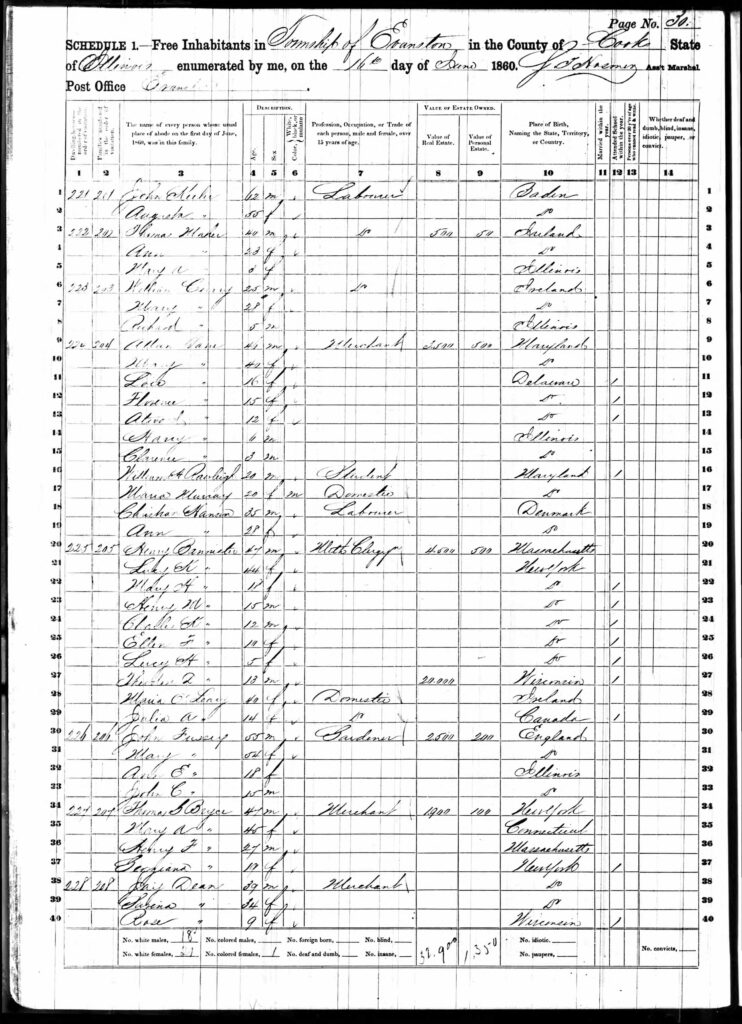

A few years after arriving in Chicago, the Vanes moved north to Evanston, where they built a house at the northwest corner of Davis Street and Forest Avenue – at what is now 305 Davis Street.[v] In the 1860 census, Maria was listed as 20 years old, meaning that she was approximately 15 years old when she first arrived in Evanston; 10 years old when she came to Chicago.[vi] Maria worked at the Vanes home as a ‘domestic’ or ‘servant’ for almost ten years before she met and married her husband George Robinson. During the early years, she attended First Methodist Church of Evanston with the Vane family. Allen and Mary Vane had converted to Methodism and were founding members of First Methodist.

As for George’s story, there’s less information on how he arrived in Evanston. All we know is that George had come to Evanston from Virginia (where he was enslaved) in 1865 or 1866 after serving as the “house servant” for Major James Ludlam in the Civil War. George may have been the first Black man to live in Evanston.

It’s unclear how Maria and George met. However, in 1868, the two were married at the Vane family home by Rev. Minor Raymond, pastor of First Methodist Church.[vii] In 1870, they petitioned to transfer their church memberships to First Baptist Church. They both may have also been members of Olivet Baptist Church in Chicago—an early Black church in the city. They were also founding members of Second Baptist Church, which was founded in 1882.

There is no record of Maria and George’s marriage. This could be for a number of reasons. Research completed by Shorefront Legacy Center found that Maria and George’s marriage was treated as spectacle by Evanston residents. There was even a sense of spectacle about Maria herself, who was called “Black Maria” and thought to have mystical powers.[viii]

For a long time, there were stories that Mary Vane and Maria were close, given the Vanes’ kindness towards Maria. However, it’s important to note that their relationship was that of an employer-employee relationship. Maybe the lack of marriage certificate can be explained by a complimentary lack of legitimacy felt by the Vanes towards Maria, as a marriage certificate would’ve offered a sense of autonomy and objective freedom. Even from a retrospective standpoint, without a marriage license, there are key details about both Maria and George’s story that are erased in favor of constructing their legacy through white people.

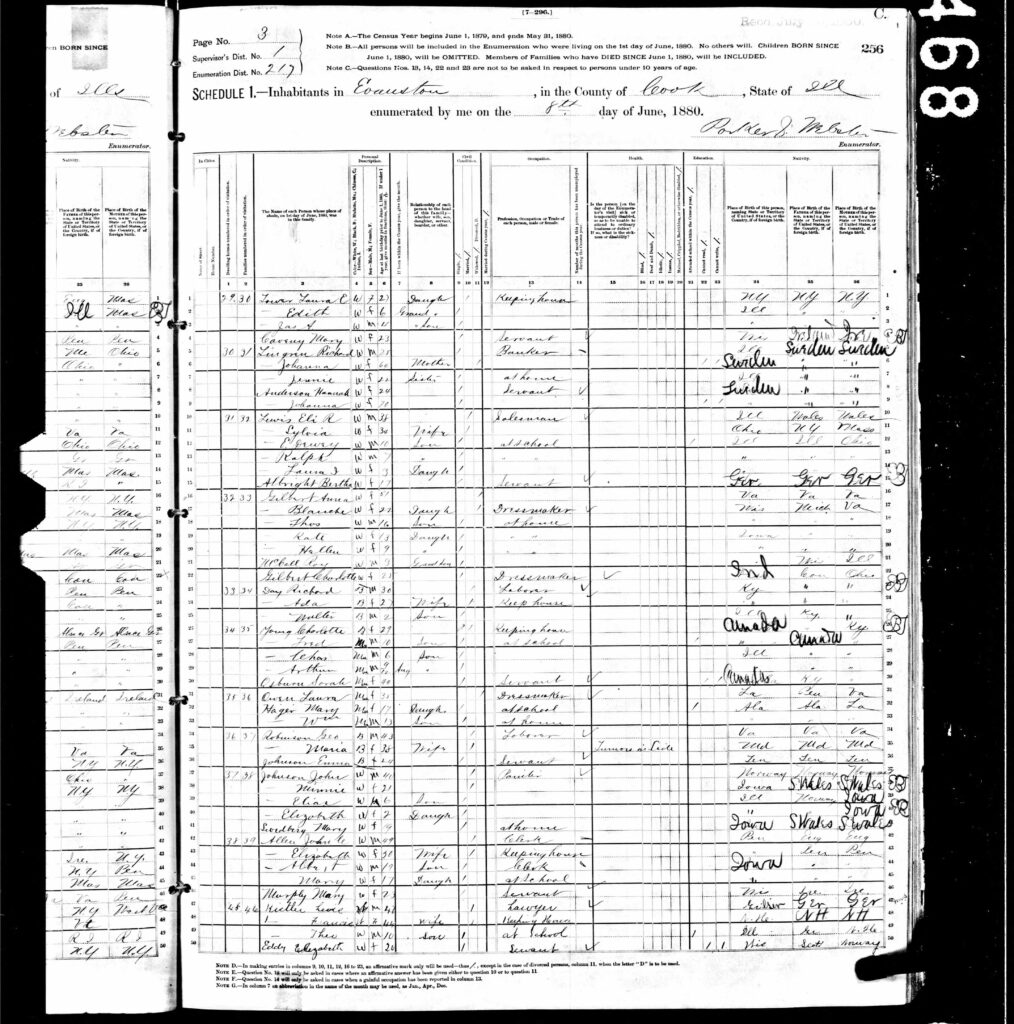

The Robinsons purchased a home at 124 Dempster Street (now 325 Dempster) in 1870 and lived there for the remainder of their lives. There were several houses grouped together in this section of Dempster going west to Judson that were owned by other Black families. The Robinson’s house still stands. George worked as a laborer, a coachman, a gardener, a milkman, and a general “man of all work.” Maria, on the other hand, is not listed as having a profession after her work for the Vane family, and in the 1880 Census is listed as being ill with “tumors on her sides”.[ix]

Interestingly enough, while they were previously thought not to have any children, in the 1900 Census Maria is listed as being the mother to two children, both of whom were no longer living. There is also a record of a black servant living with the Robinsons named Emma Johnson who is listed as being born in Tennessee in 1856.[xi]

Maria died in 1901 and was buried in the Vane family plot in the all-white section of Rosehill Cemetery,[xii] while George, who died in 1911, was buried in the “colored” plot in the same cemetery. Mary Vane had been dead by this time for almost 30 years, and Allen Vane had even remarried. Why would George consult with the Vane family to bury Maria alongside Mary? The families must have remained connected over these many years. Maria’s burial in the Vane family plot indicates a closer relationship.

In the coming weeks of summer, I will continue to write about other instances of fragile white-black alliances in Evanston and how the power dynamics established between all parties influence how we retrospectively view them in history.

Sources for more information:

Chicago History Museum project on Black residents of early Chicago

[i] See attached Illinois 1850 Census Record from Ancestry.com.

[ii] Evanston Index, May 19, 1900, 3.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] See attached Maryland 1850 Slave Schedule Record from Ancestry.com.

[v] All of this information about the Vane’s residences is from the 2016 EHC House Walk booklet.

[vi] See attached Illinois 1860 Census Record from Ancestry.com.

[vii] Evanston Index, May 19, 1900, 3.

[viii] Yarvis, Olivia. “First Black Evanston Resident’s Home Named Heritage Site.” The Daily Northwestern, 6 Aug. 2020.

[ix] See attached Illinois 1880 Census Record from Ancestry.com.

[x] Illinois 1900 Census.

[xi] See above Illinois 1880 Census Record from Ancestry.com.

[xii] Evanston Index, May 19, 1900, 3.