The League of Women Voters of Evanston held its first meeting on March 28, 1922 – 100 years ago. The National League of Women Voters was founded on February 14, 1920 (in Chicago) and the 19th amendment was ratified on August 26, 1920. Why did it take two years for the Evanston league to form? What is the story of its founding?

Women’s Suffrage in Illinois

Most women’s suffrage timelines start with the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York, and the first suffrage activities in Illinois took place in the 1850s. In the late 1800s the temperance movement was the leading reform movement for women, and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, led by Evanston’s own Frances Willard, endorsed women’s suffrage in 1881.

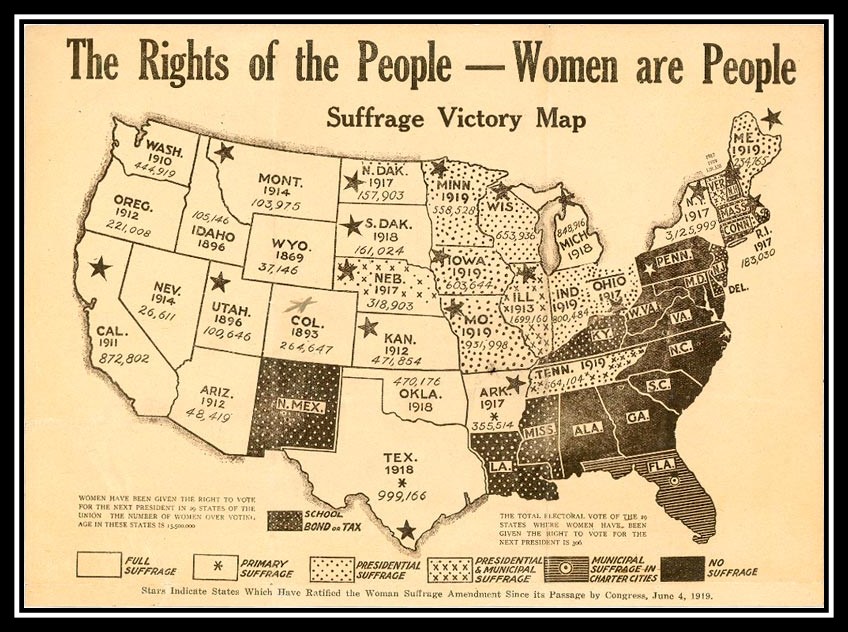

Some states granted limited voting rights to women in the 1890s. Illinois women could vote in school elections starting in 1891; school involvement was seen as closely linked to their roles as mothers. In 1913 their rights were broadened to include voting for additional offices, including president. Illinois was the first state to ratify the 19th amendment and the location of important moments in suffrage history including the founding of the National Women’s Party and, as mentioned, the founding of the League of Women Voters.

Debating the League’s Mission

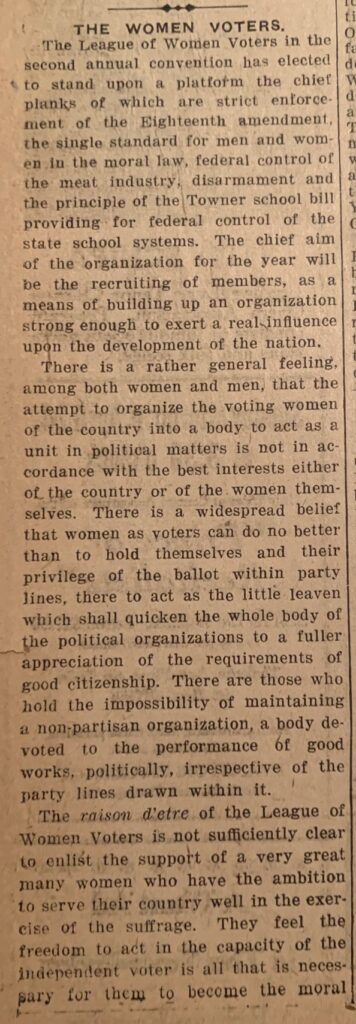

At its founding, it wasn’t fully clear what the LWV would do, and discussions and debates about its mission began immediately. Although women in many states could already vote for at least some offices, many had not yet fully embraced the idea of themselves as voters, and the LWV could provide a place for women to learn about and explore this new identity. It is hard for us to imagine, but the idea that the voices of women were not needed or wanted in the political process was ingrained and hard to shake.

The LWV could also provide a place for women to continue their work for women’s rights more broadly, as voting was just one of many ways their lives were restricted based on gender. Through the LWV women could also advocate for such issues as mother and child welfare. And women could rely on the LWV for voter information and education outside the political parties that had long excluded them. Each of these roles was important and each could solely occupy the work of the organization. Deciding which to focus on was the challenge of the early years, nationally and at the state and local levels. At the founding convention of the Illinois League of Women Voters in October 1920, a symposium was held on “The LWV and What It Can Accomplish.”[i]

Debates about focus were accompanied by another big question: Was there really a need for a women voters’ organization? From the beginning the LWV thought of itself as nonpartisan, like its predecessor suffrage organizations where Democrat and Republican women worked together. Some women, though, saw no need for a nonpartisan voters’ organization; women should just join the party of their choice and work within it for things they thought important. For issues of special interest to women, they could also continue to work through existing groups. In Evanston, for example, women had been working together across party lines for many years in organizations like the WCTU and the Woman’s Club of Evanston.

A League in Evanston

In Fall 1921 debates about the role of the LWV came to a head at the national convention. Voter turnout for the 1920 presidential election had been low with many women staying out of the process entirely. This surprised League members, and it became clear that getting other women registered to vote and to the polls was going to take more work and focus than originally thought. The need for nonpartisan voter education became paramount, and the national league began to see its role more clearly. While it would continue to work broadly for women’s issues and rights, its focus would be on creating an educated electorate (male and female) and getting women involved in politics.

It is this focus that got the attention of Evanston women and galvanized them to form the LWVE. The stated goal of the organization was “to ensure that correct information was given to all women voters of Evanston.”[ii] One early activity was to help organize a Citizenship School (see last month’s Intercom). After its founding meeting on March 28th, the LWVE invited representatives from 70 Evanston women’s organizations to a luncheon at the Woman’s Club of Evanston to form the coalition and begin the work.

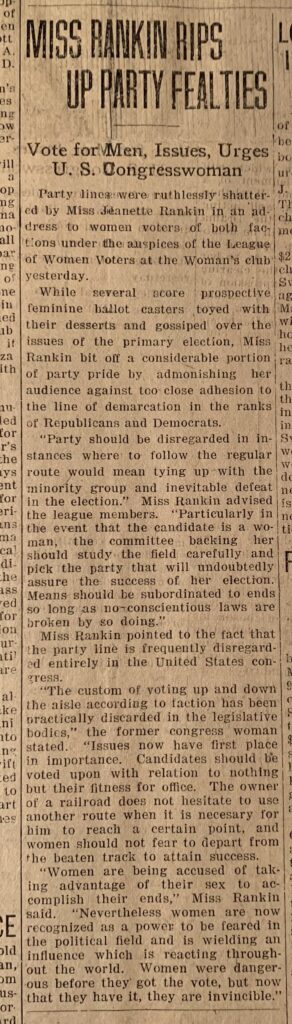

The guest speaker for the April 2nd luncheon was Jeannette Rankin, the first woman elected to the U.S. Congress. Her speech that day made the front page of the Evanston Index. She is quoted as saying: “Women are being accused of taking advantage of their sex to accomplish their ends. Nevertheless women are now recognized as a power to be feared in the political field…Women were dangerous before they got the vote, but now they have it, they are invincible.”[iii]

For more about the Evanston League and its current work – visit its website – https://www.lwve.org

Secondary Sources

Kristi Andersen. After Suffrage: Women in Partisan Electoral Politics before the New Deal. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1996.

Louise M. Young. In the Public Interest: League of Women Voters, 1920-1970. New York: Greenwood Press, 1989.

[i] The Woman Citizen, October 16, 1920, p 551.

[ii] Evanston News Index, March 16, 1922.

[iii] Evanston News Index, April 4, 1922, p 1.